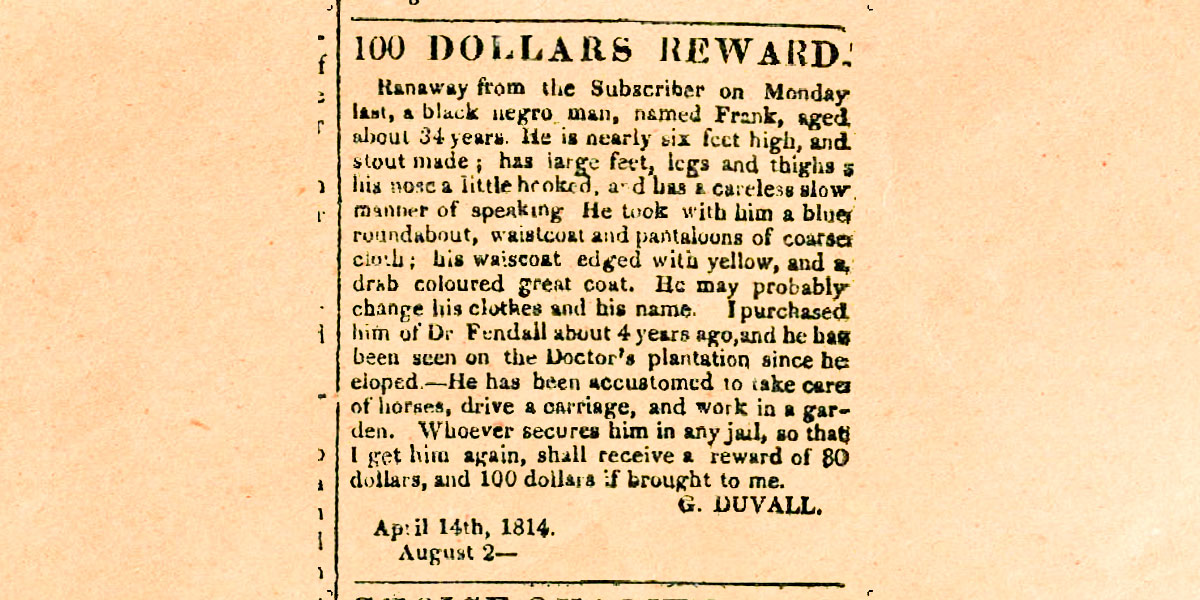

100 Dollar Reward was open from February 2018 until August 2018. The exhibit examined slavery in Georgetown from its founding in 1751 to 1830 and explored the lives of enslaved workers in an urban area and how their experiences differed from the chattel slavery of plantation life. We invite visitors to examine the story of slavery in the our nation’s capital and reflect on the founding ideals of freedom and liberty in a new nation that kept millions in bondage.

Slavery Takes Root

The institution of slavery shaped the economy and culture of the North American Colonies beginning in 1619 Jamestown, Virginia where 20 Africans were sold into slavery. Slavery is often portrayed as a uniform institution throughout North America, but the experiences of enslaved persons varied widely. We invite you to examine the institution of slavery in Georgetown, a well-established town, during the creation and fledgling years of the District of Columbia (1790-1830), and when the Nourse household occupied Dumbarton House (1804-1813).

The Nourse household consisted of indentured white, free black, and enslaved workers (most of the records do not indicate which individuals were free and which were enslaved). The information about at least 18 workers comes from census data and the Nourse family papers. Yet, research is ongoing, as we hope to obtain a better understanding of the daily tasks and personal life of the free and enslaved workers who labored on the property.

Slavery and the Tobacco Trade

Hail thou inspiring plant! Thou balm of life, Well might thy worth engage two nations’ strife; Exhaustless fountain of Britannia’s wealth; Thou friend of wisdom and thou source of health. -from an early tobacco label Tobacco, that outlandish weed It spends the brain, and spoiles the seede It dulls the spirite, it dims the sight It robs a woman of her right.

– Dr. William Vaughn, 1617

Tobacco was the principal source of wealth in colonial Maryland. It permeated all facets of life, serving as the main currency and influencing economic and political institutions. As European demand for tobacco increased, so did demand for enslaved Africans to harvest the crop. By the time Georgetown was founded in 1751, Africans who were forcibly taken to the region, made up over a third of Maryland’s population.

William Tatham, An Historical and Practical Essay on the Culture and Commerce of Tobacco, 1800, Courtesy of the Library of Congress

Slavery became entrenched in Georgetown’s economy, as the area encompassed every aspect of the tobacco trade. Cultivating tobacco was labor intensive and enslaved field workers labored year round to grow and harvest the plant. Tobacco grown on Maryland plantations upriver from Georgetown, were tightly packed into large wooden casks called hogsheads and rolled down High Street, now Wisconsin Avenue to tobacco warehouses along the waterfront to be exported to both domestic and foreign ports. By the mid-1700s, Georgetown had become one of the largest tobacco ports in North America.

Cartouche on Fry-Jefferson Map, 1755, Courtesy of the Library of Congress

The Port City: Center of the Slave Trade

Established as a port city for the colony of Maryland, Georgetown was a hub not only for the tobacco trade, but also the slave trade. Taverns were the site of slave auctions and housed enslaved workers in crowded pens while they awaited sale. In 1760, John Beattie established a slave auction site on Gay Street (now O Street). He also conducted auctions at Montgomery Tavern on High Street (now Wisconsin Avenue). In the 1820s taverns located on High and Bridge Streets (now Wisconsin and M Streets) were the center of the slave trade in Georgetown.

Image: The Georgetown waterfront, circa 1795, Courtesy of the Library of Congress

Jesuit priests, who ran Georgetown College were actively involved in the slave trade, relying on tobacco plantations and the sale of enslaved workers to finance the school’s operations. In 1838, the College sold 272 men, women, and children to southern plantation owners. This sale, like most, separated children from parents, husbands from wives, brothers from sisters.

Image: “The Potomac, Analostan Island, and Georgetown College” by Caroline Nourse, 1838

King Cotton and the Slave Trade

“One day I went to see the “slaves’ pen”–a wretched hovel, “right against” the Capitol, from which it is distant about half a mile, with no house intervening. The outside alone is accessible to the eye of a visitor; what passes within being reserved for the exclusive observation of its owner, (a man of the name of Robey,) and his unfortunate victims. It is surrounded by a wooden paling fourteen or fifteen feet in height, with the posts outside to prevent escape, and separated from the building by a space too narrow to admit of a free circulation of air. At a small window above, which was unglazed and exposed alike to the heat of summer and the cold of winter, so trying to the constitution, two or three sable faces appeared, looking out wistfully to while away the time and catch a refreshing breeze; the weather being extremely hot. In this wretched hovel, all colors, except white–the only guilty one–both sexes, and all ages, are confined, exposed indiscriminately to all the contamination which may be expected in such society and under such seclusion. The inmates of the gaol, of this class I mean, are even worse treated; some of them, if my informants are to be believed, having been actually frozen to death, during the inclement winters which often prevail in the country.”

-Edward Strutt Abdy, Journal of a Residence and Tour in the

United States of North America,…, 1833-1834

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

By the 1820s, tobacco was on the decline and grains, such as, wheat replaced tobacco as the main cash crop. Grains were not as labor intensive to cultivate and planters no longer needed a large enslaved labor force. While tobacco was waning, cotton was booming. The invention of the cotton gin made cotton profitable to grow, as it allowed cotton fibers to be quickly separated from seeds. Cotton became the primary cash crop of the Deep South and demand for enslaved labor to cultivate cotton fields increased dramatically. Maryland planters no longer cultivating tobacco and residents in the new Federal City took advantage of the new market for enslaved workers.

for ginning cotton in 1794

Courtesy of National Archives and

Records

The District of Columbia became the center of slave trade, as it provided conveniently located waterways to transport enslaved workers from the Upper South to the Deep South. It is estimated that nearly one million people were forcibly moved from the Upper South to the Lower South from the 1820s until slavery was abolished. In Georgetown, taverns, including Union Tavern, McCandless Tavern, and the Montgomery Tavern, located on High and Bridge Streets (now Wisconsin and M Streets) were the site of slave auctions and housed enslaved workers in crowded pens while they awaited sale. Rather than selling their excess labor force, some owners found it more profitable to hire them out to the hotels, restaurants and boarding houses in Washington City, especially when Congress was in session. Enslaved workers were also hired out in the building trade, including construction of the White House, the U.S. Capitol, and most other

buildings in the city.

The Enslaved and Free Community of Georgetown

Slavery in urban areas was different from its counterpart on rural plantations. Although rife with its own horrors, urban slavery provided different experiences from the chattel slavery of plantation life. Throughout the Federal period, free and enslaved blacks, made up a third of Georgetown’s population. The US census of 1800 reports 1,449 slaves and 277 free blacks from a total population of 5,120. Over this period, the number of enslaved workers decreased, while the number of free blacks increased – becoming the majority within the black population by 1830. The large number of enslaved workers, as well as, a significant number of free blacks living in a small area was a distinct difference from rural plantations.

Letter from Joseph to Maria, May 15th, 1785

The urban labor system was dependent on the mobility of enslaved workers. At Dumbarton House, like other urban estates, the primary duties of enslaved workers allowed for time away from the property – enslaved women cooked, cleaned, laundered, and raised children, while men served as coachmen, butlers, or gardeners. Juba, the enslaved gardener at Dumbarton House, ran errands and served as a travel escort. Another enslaved worker, Bacchus worked as a coachmen. These duties provided time away from the confines of Dumbarton House and the ability to interact with other enslaved and free blacks. Unlike enslaved workers on rural plantations who, because of the physical size of farms, were often limited to interaction with people of a single household or neighboring farms, enslaved workers in an urban environment had opportunities to congregate with a larger network of both enslaved and free blacks.

Free and enslaved blacks were able to establish their own community, including churches and schools. Free black neighborhoods and households were central to urban enslaved workers, as the urban environment afforded little privacy and these households provided refuge away from owners. At Tudor Place, a neighboring estate, the enslaved cook, Patty Allen “lived out” or off the property with her husband who was free. As described by Britannia Peter Kennon of Tudor Place, “There was old Patty, who was the cook—Every night she went home to her husband, who was free, and every morning-she was in the kitchen at crack of day.”

Sites in Georgetown:

- GEORGETOWN MARKET: Enslaved and free blacks congregated here to purchase and sell goods for the household

- GORDON’S WAREHOUSE: Established in 1745 as an official tobacco inspection station and warehouse

- FERRY WHARF: Ferry that ran between Georgetown and Mason’s Island to transport people between Georgetown and Alexandria

- MONTGOMERY TAVERN: Functioned as a slave auction site and depot

- POST OFFICE AND CUSTOM HOUSE: With no home delivery service, this was one of the busiest blocks in Georgetown

- HERRING HILL: Free and enslaved black neighborhood

- TUDOR PLACE: In 1820 there were 6 enslaved adults and 8 enslaved children under the age of 14 working

- MT. ZION UNITED METHODIST CHURCH: In 1816 black members of the

Montgomery Street Church purchased land and built The Meeting House –

called the Mt. Zion United Methodist Church today - YARROW MAMOUT RESIDENCE: Brought over from Africa in 1752, Yarrow Mamout purchased his own freedom at the age of 60

- GEORGETOWN UNIVERSITY: Founded in 1791, the school used enslaved labor through the mid-19th century

- GEORGETOWN VISITATION: Established in 1799 as a school for young women, many of the resident nuns and students brought their enslaved workers to work at the school

Mount Zion/Female Union Band Society Cemetery

Today, the Mount Zion/Female Union Band Society Cemetery encompasses three acres of land and includes two burial grounds: the Mount Zion Cemetery and the Female Union Band Society Cemetery. The Mount Zion Cemetery was established in 1808 as a burial ground for white parishioners of the Montgomery Street Methodist Church (now Dumbarton Street United Methodist Church) and their enslaved workers. The Church was one of the few that accepted both white and black parishioners. In 1816, in response to racial codes that segregated blacks, 125 black members formed their own church, “The Ark” or “The Meeting House” (now Mount Zion United Methodist Church).

What sites in your community are in need of preservation?

What stories do they tell?

What would be lost if they were not saved?

In 1848, the Female Union Band Society was formed by a group of African American and Native American women. It served as a benevolent society and pledged a grave for each member. As a way to fulfill this pledge, approximately 1.5 acres of land was purchased along the western border of the existing cemetery and named the Female Union Band Society Cemetery. Research has indicated that possibly thousands of individuals, the majority free or enslaved blacks, are buried here.

In 2012, the DC Preservation League listed the Cemetery as one of the most endangered sites in Washington, D.C. Currently, the Mount Zion/Female Union Band Society Historic Memorial Park Foundation, with community support, is working to rehabilitate and interpret the Cemetery.

“I had resided but a short time in Baltimore before I observed a marked difference, in the treatment of slaves, from that which I had witnessed in the country. A city slave is almost a freeman, compared with a slave on the plantation. He is much better fed and clothed, and enjoys privileges altogether unknown to the slave on the plantation. There is a vestige of decency, a sense of shame, that does much to curb and check those outbreaks of atrocious cruelty so commonly enacted upon the plantation. He is a desperate slaveholder, who will shock the humanity of his non-slaveholding neighbors with the cries of his lacerated slave. Few are willing to incur the odium attaching to the reputation of being a cruel master; and above all things, they would not be known as not giving a slave enough to eat. Every city slaveholder is anxious to have it known of him, that he feeds his slaves well; and it is due to them to say, that They wanted to send the impression that slaves were not treated so poorly.. There are, however, some painful exceptions to this rule.”

-Frederick Douglass, 1845