Death and Mourning in the Federal Era

“Our new Constitution is now established, and has an appearance that promises permanency; but in this world nothing can be said to be certain, except death and taxes,” wrote Benjamin Franklin in 1789. Death comes for us all, but for the denizens of the Federal Era, the certainty of death was more immediate than it is today. The average life expectancy was under forty, and child mortality rates were high, with 46 percent of children not surviving until their fifth birthday.

Dumbarton House’s occupants are no exception: Émilie and André Pichon’s first son, Louis, born in 1803, died the following year of cholera. The Nourse family, who purchased the property in 1804, also experienced similar tragedy: of their six children, born between 1785 and 1800, only two survived to adulthood, with their eldest daughter, Anna Maria Josepha, succumbing to what is thought to be tuberculosis at the age of 20.

These deaths all took place before the advent of photography, so while the Victorian concept of “death portraits” had yet to be invented, mementos were still an important part of remembering the dead, especially since embalming as we know it was not yet practiced and the dead needed to be buried quickly. These mementos often took the form of jewelry, specially created to commemorate the passing of a loved one. The Dumbarton House collection features several of these, including rings, pins, and lockets.

This ring, set with jet, is engraved “John Julius Pringle Nat. Oct. 18 1784 Ob. 1st. Aug. 1807.” (John Julius Pringle, born October 18, 1784, died August 1st 1807). It likely belonged to the family of John Julius Pringle in Charleston, SC.

This gold ring is engraved “F.B. Ob. Nov. 24, 1779, Ae. 22ys.” (F.B. died November 24, 1779, aged 22 years). Unfortunately, both the original owner and the full name of “F.B.” have been lost to time.

Another common mourning practice up until the 20th century was collecting the hair of the deceased, often to be incorporated into specific items of mourning jewelry. While this practice, known as “hairwork” rose to its greatest prominence during the Victorian era, hairwork has been documented from the Middle Ages onwards. While the body begins to decompose immediately after death, hair does not, making it an excellent option for those looking for a physical link to their departed loved ones.

Once collected, the hair could take many forms. If only a small amount of hair was available, it could be turned into cut-hair work, using small lengths of hair to create a picture, such as in this mourning ring from 1772, in which the hair was set in a wreath around the picture of an urn bearing the initials “E P”. This is unmistakably a mourning ring, as the band exterior is inscribed “Esther Pyatt OB: 27 June 1772 AET 22.” (Esther Pyatt died June 27, 1772, aged 22 years). The band interior is inscribed “J. Pyatt Married E. Allston 30 April 1769.” This ring likely belonged to Esther Allston Pyatt’s husband, and would have been created after her death in 1772.

Of course, rings were not the only pieces of jewelry used to commemorate the deceased. Brooches were also popular—one of their benefits being that they allowed more elaborate artwork to be created, such as on this mourning pin from c. 1780-1790 Philadelphia. On this brooch, the deceased’s hair was finely cut and ground before being turned into paint, which was used to paint the picture on the brooch. This technique was also likely employed to paint the urn in the center of the Pyatt ring above.

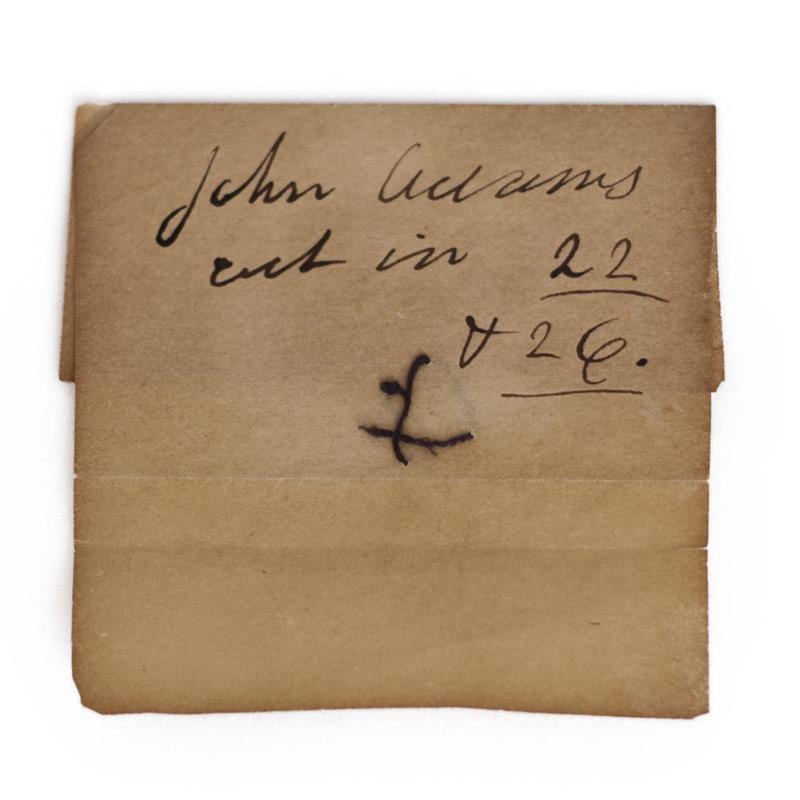

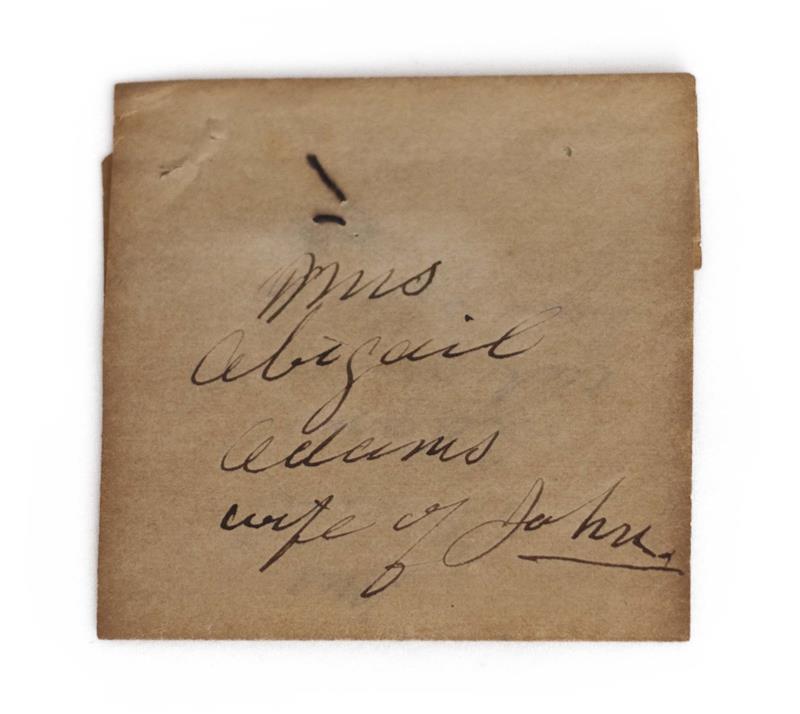

Sometimes, hair would be collected due to the owner’s fame, as can be seen with these two envelopes from the Dumbarton House archives: originally, they probably contained hair samples from John and Abigail Adams. While they may have had sentimental value, they were more likely preserved because of their ties to the former President and First Lady.

Though popular for mourning, hairwork could also be used to remember those who were not yet dead. Two lockets in Dumbarton House’s collection were created while their subjects were still alive: they feature small ivory portraits, clearly painted while their sitters were still living. These lockets are more likely to have been mementos for family or loved ones when their subjects were away.

This miniature, featuring a portrait of Daniel Carroll Brent on the front, has two pieces of hairwork: one buckled band circling the portrait on the front, and an interwoven checkerboard of hair on the back, set with small gold stars. When we examined the piece, we noticed that the interwoven back piece contains hair from two different people, and that the lighter and finer-textured hair appears to match the woven band on the front. While we do know that the miniature, attributed to Raphaelle Peale, is of Daniel Carroll Brent, the sources of the hair are now unknown.

The most recent piece of hairwork in Dumbarton House’s collection is in this miniature of prominent DC lawyer William Redin, likely painted around 1841, and features Redin’s portrait on the front, with a window for a checkerboard of dark brown hair on the reverse. Given that the hair is all one color, and a good match for Redin’s own, it is likely that this miniature was a token or memento for a loved one during his life.

Hairwork gained great popularity during the Victorian era, during which the symbols and practices of mourning were became more codified and complex. Additionally, the practice of hairwork as a purely decorative art also gained prominence. Unfortunately, Dumbarton House’s collection does not contain any later pieces of Victorian hairwork, which became increasingly elaborate, and often included floral motifs, three-dimensional designs, and could be quite large-scale. The popularity of hairwork experienced a sharp decline during the 20th century, but has experienced a small revival in recent years, with both human and pet hair being used to remember the deceased.

While keeping pieces of our loved ones’ hair may strike many of us as eccentric or even downright creepy, it must be remembered this practice was not an unusual one in the past. Although some of this can be attributed to a society more familiar with death than ours is now, familiarity with death does not mean becoming desensitized to it: when Louis Pichon died, his mother Émilie wrote to her family that she could not bear to remain in the house where her son had been born, and the Pichons left Dumbarton House soon thereafter. In a world where loss hurt just as much as it does in ours, but where images or other reminders of the deceased were far fewer, hairwork helped comfort the living through their grief—and for many, it might have been the only physical link to a person who had become a memory.