Observations on Ice Creams

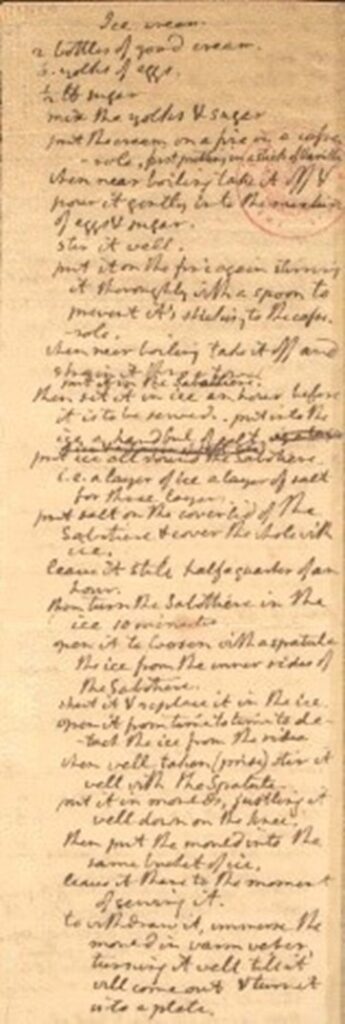

“It is the practice with some indolent cooks, to set the freezer containing the cream, in a tub with ice and salt, and put it in the ice house; it will certainly freeze there; but not until the watery particles have subsided, and by the separation destroyed the cream. A freezer should be twelve or fourteen inches deep, and eight or ten wide. This facilitates the operation very much, by giving a larger surface for the ice to form, which it always does on the sides of the vessel; a silver spoon with a long handle should be provided for scraping the ice from the sides as soon as formed; and when the whole is congealed, pack it in moulds (which must be placed with care, lest they should not be upright,) in ice and salt, till sufficiently hard to retain the shape—they should not be turned out till the moment they are to be served. The freezing tub must be wide enough to leave a margin of four or five inches all around the freezer, when placed in the middle—which must be filled up with small lumps of ice mixed with salt—a larger tub would waste the ice. The freezer must be kept constantly in motion during the process, and ought to be made of pewter, which is less liable than tin to be worn in holes, and spoil the cream by admitting the salt water.

Mary Randolph, The Virginia Housewife, 1824

Library of Congress

Ice cream was first invented in the seventeenth century as a dish for kings. Beginning in the eighteenth century, English cookbooks include recipes for ice cream, starting in 1718 with Mrs. Mary Eales, the royal confectioner to Queen Anne. Recipes contained advice about how best to freeze the cream mixture to create ice cream. Mrs. Elizabeth Raffald’s cookbook of 1775 says to set the mixture: “in a tub of ice broken small, and a large quantity of salt put amongst it, when you see your cream grow thick round the edges of your tin, stir it, and set it in again till it grows quite thick, when your cream is all froze up, take it out of your tin, and put it into the mould you intend it to be turned out of, then put on the lid, and have ready another tub with ice and salt in as before, put your mould in the middle, and lay your ice under and over it, let it stand four or five hours.”

The French invented a tool to do this called a sarbotiere, but other options were available to those who could not afford a fancy foreign import. An English cookbook author, Hannah Glasse, recommended buying “two pewter basons” instead. Pewter was preferred because it was strong. Mrs. Mary Randolph’s 1824 cookbook The Virginia Housewife says, “The freezer must be kept constantly in motion during the process, and ought to be made of pewter, which is less liable than tin to be worn in holes, and spoil the cream by admitting the salt water.” Salt is necessary to lower the freezing point of the ice. Without it, the cream will never get cold enough to harden sufficiently to form ice cream.

The first official account of ice cream in North America comes from a letter written in 1744 by a guest of Maryland Governor William Bladen. The first advertisement for ice cream in this country appeared in the New York Gazette on May 12, 1777, when confectioner Philip Lenzi announced that ice cream was available “almost every day.” However, during this time ice cream was reserved for the wealthy due to the expensive ingredients required to make it. Anyone who owned a cow could have access to heavy cream, but sugar exported from the Caribbean islands and ice – stored in ice houses during the summer – were harder to obtain. Sugar was so expensive because the process of turning sugar cane into sugar is extremely labor intensive. On Caribbean islands, enslaved Africans labored in extreme heat and dangerous conditions to make the sugar that generated enormous wealth for the white Europeans selling it.

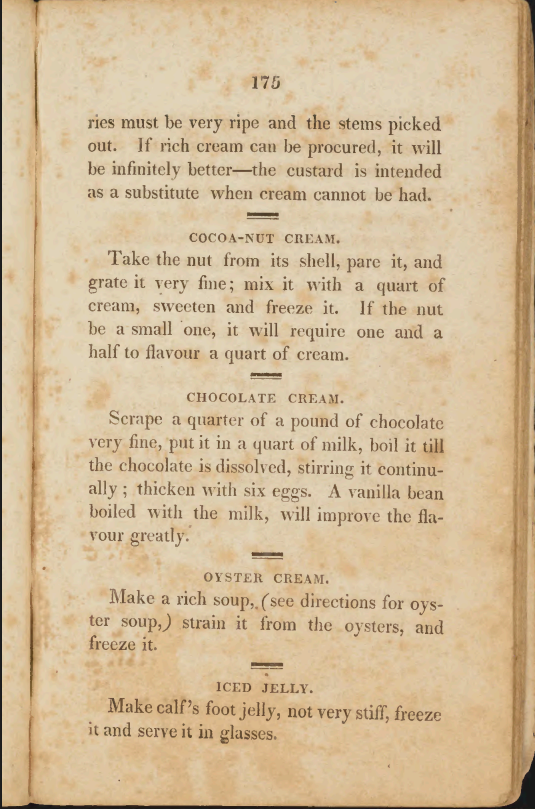

In the 1800s, ice cream was made in a wide variety of flavors including

Library of Congress

- Artichoke with pistachios and candied orange

- Cheese (parmesan and gruyere)

- Crumbled macaroons

- Cinnamon

- Caramel

- Tea

- Musk

- Anise seed

- Fennel

- Chervil

- Tarragon

- Celery

- Parsley

- Ginger

- Lemon

- Pomegranate

- Pistachio

- Jasmine

- Orange flower

- Elderflower

- Rose petals

Perhaps the strangest flavor was oyster ice cream (found in Mary Randolph’s cookbook) – a flavor many describe as Dolley Madison’s favorite, although no evidence suggests this was true. It was essentially frozen oyster chowder, unsweetened with the oysters strained out. In some ways, ice cream was considered a savory dish. Some Victorians even paired their ices with the meat or fish course. Mrs. Sarah Rorer suggested serving her cucumber sorbet with “boiled cod or halibut.” Her gooseberry sorbet was “usually served at Christmas dinner with goose.” Naturally, she served mint sherbet with lamb or mutton and apple ice with roasted duck, goose, or pork.

Often the ices were molded into fanciful shapes like fish, chickens, cauliflower, pineapples, and, especially, asparagus. Ice cream could also be served at the table from an ice pail, which kept it cold—and allowed it to be on display until it was served.

The porcelain ice pail in Dumbarton House’s collection dates from the 1820s, and comes in three parts: the main body holds crushed ice below a bowl insert which holds the ice-cream or fruit ice; the top was piled with additional ice to keep the whole cool. It would have been placed on the dining table, allowing the ice cream to remain cold until the moment it was to be served.

The Founding Fathers helped popularized ice cream in America. Records kept by a Chatham Street, New York, merchant show that President George Washington spent approximately $200 for ice cream during the summer of 1790. A 1796 inventory lists “2 freising molds” in the Monticello kitchen, so his servants were making ice cream at least that early. When he was president, Jefferson had an icehouse built for the President’s House—called the White House today—and on Independence Day in 1806, hired a servant to turn the ice cream maker all day. In 1813, Dolley Madison served a magnificent strawberry ice cream creation at President Madison’s second inaugural banquet at the White House.

“When ice creams are not put into shapes, they should always be served in glasses with handles” (Mary Randolf, The Virginia Housewife, 1820s). Ice cream melted quickly in an age before air conditioning and refrigeration, and the handles were meant both to prevent the transfer of heat from the hands, and for ease of drinking the liquid once the ice cream inevitably melted.

The Founding Fathers helped popularized ice cream in America. Records kept by a Chatham Street, New York, merchant show that President George Washington spent approximately $200 on ice cream during the summer of 1790. Thomas Jefferson, the Founding Father most often associated with ice cream, had “2 freising molds” in the kitchen during his 1796 inventory, so his servants were making ice cream at least that early. When he was president, Jefferson had an icehouse built for the President’s House—called the White House today—and on Independence Day in 1806, hired a servant to turn the ice cream maker all day. In 1813, Dolley Madison served a magnificent strawberry ice cream creation at President Madison’s second inaugural banquet at the White House.

A desire for ice cream is one reason wealthy Americans built ice wells – rooms dug out of the ground to keep ice (cut from lakes in the winter) frozen all summer. The ice would often be packed with sawdust or straw to help insulate it and prevent it from melting. Joseph Nourse had his ice house relocated to his property in Georgetown, called Dumbarton House today!

Until the nineteenth century, ice cream remained a rare and exotic dessert enjoyed mostly by the elite. In 1843, Nancy M. Johnson in Philadelphia received a patent for an “artificial freezer” consisting of a wooden bucket with a smaller metal cylinder inside. The interior metal cylinder contained a dasher that was turned by a crank handle. Rock salt and ice would be combined in the bucket surrounding the mixture of cream, sugar, eggs and other ingredients inside the cylinder. When the handle was cranked, the mixture turned and slowly began to freeze from the ice and salt. Additionally, the dashers scraped the ice cream from the sides of the can. The ice cream churner made this frozen treat easier to make and changed the industry forever.

Ice cream production continued to increase because of technological innovations, including steam power, mechanical refrigeration, the homogenizer, electric power and motors, packing machines, and new freezing processes and equipment. In addition, motorized delivery vehicles dramatically changed the industry. Due to ongoing technological advances, today’s total frozen dairy annual production in the United States is more than 1.6 billion gallons.

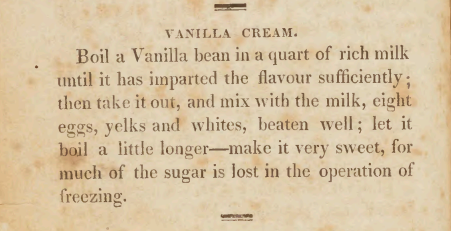

If you’d like to add to the United States’ ice cream production, you can try following Mary Randolph’s recipe for vanilla ice cream from 1824, or use the modernized recipe provided below:

- 2 cups heavy cream

- 1 cup whole milk

- 2/3 cups granulated sugar

- Pinch of sea salt

- 6 egg yolks

- 2 tsp. vanilla extract or vanilla bean paste, OR 1 vanilla bean, split lengthwise

Step 1: If using vanilla bean: in a small pot, simmer heavy cream, milk, and vanilla bean. Let steep until cool. Scrape vanilla seeds into mixture and discard pod. Add sugar and salt, and reheat until sugar dissolves.

If using vanilla extract or paste: in a small pot, combine cream, milk, vanilla extract/paste, sugar, and salt and simmer until sugar dissolves.

Step 2: In a medium bowl, whisk yolks. Whisking constantly, slowly add hot cream mixture to the yolks to create a custard.

Step 3: Return custard to pot and cook on medium-low heat, stirring constantly to prevent bottom from burning, until mixture is thick enough to coat the back of a spoon.

Step 4: Strain into a bowl and cool to room temperature, then chill at least 4 hours. Churn in an ice cream maker according to manufacturer’s instructions, or freeze, stirring to break up ice crystals.

Question: Should you stir the ice cream while it is freezing?

This answer has two parts. Stirring adds air to your ice cream, which can help make it feel light. However, too much air and your ice cream will melt quicker. Premium ice creams and gelato typically have less air, which is why a pint of premium ice cream can weigh as much as a quart of budget ice cream.

For some more information, ice cream’s creaminess depends on the size of the ice crystals that form during freezing. Rapid chilling and constant churning encourage the water in the ice cream mixture to form tiny ice crystals and therefore feel smoother and creamier than ice cream that has fewer, larger crystals. Constant churning helps keep the crystals moving as they chill, so they have less time to attach to one another and form large clusters.

Finally, don’t expect a store-bought ice cream texture. Ice cream manufacturers often rely on added ingredients to keep their products creamy like plant-based stabilizers such as guar gum and locust bean gum (derived from tree seeds), carrageenan (from seaweed), and pectin (from fruit).

Question: Do you have to include eggs?

No! Many historical recipes do not include eggs, but they will help create a thicker, creamier custard flavor and texture to your ice cream, especially if you are not using a machine (hand-powered or electric) to churn your ice cream.

Written by Sheridan Small, Director of Education

Updated July 2025 by Isabella Kiedrowski, Archives & Collections Manager

Sources:

- Colonial Williamsburg

- Grahn, Emma. “Keeping your (food) cool: From ice harvesting to electric refrigeration.” O Say Can You See? Stories from the Museum. National Museum of American History, April 29, 2015.

- Ice Cream, Thomas Jefferson Encyclopedia, Monticello

- Quinzio, Jeri. “Asparagus Ice Cream, Anyone?” Gastronomica, May 5, 2002.

- Schultz, Colin. “George Washington Liked Ice Cream So Much He Bought Ice Cream-Making Equipment for the Capital,” Smithsonianmag.com, March 28, 2014.

- “Legends and Myths of Ices and Ice Cream History.” What’s Cooking America?