Integrated Pest Management in a Historic House Museum

A few weeks after starting as Archives & Collections Manager at Dumbarton House, I was cleaning the period rooms when I saw the last thing a museum professional wants to see: a moth, sitting on a wool blanket. Seeing a moth in a museum is bad news: much like rodents and cockroaches, seeing one means that there are inevitably a few dozen of its friends lurking nearby. With some trepidation, I peeled back the blanket to reveal—you guessed it—more moths. And just like that, we had an infestation.

The moth we were dealing with, and the one that makes collections managers everywhere wish that mothballs were still a legal weapon in our arsenals, was the webbing clothes moth, or Tineola bisselliella. The adult moths measure up to 8.5 mm (0.3 inches) in length, and are light gold in color. The larvae—who do the real damage—are cream colored with brown heads and measure 13 mm (0.5 inches) in length.

The webbing clothes moth starts out as a small ivory egg, about 1 mm in size. Eggs hatch 4-10 days after laying in warm environments, and up to 30 days after laying in cold ones. Once hatched, the larvae spend the next 35 days eating their way through whatever protein-based substances they can find. Although we generally associate the damage caused with adult moths, the damage is actually done in the larval stage—the adult moths, who live 15 to 30 days, do not eat. They simply reproduce, lay eggs, and die, starting the cycle all over again. If the life cycle is interrupted at any stage, the chances of an infestation continuing decrease.

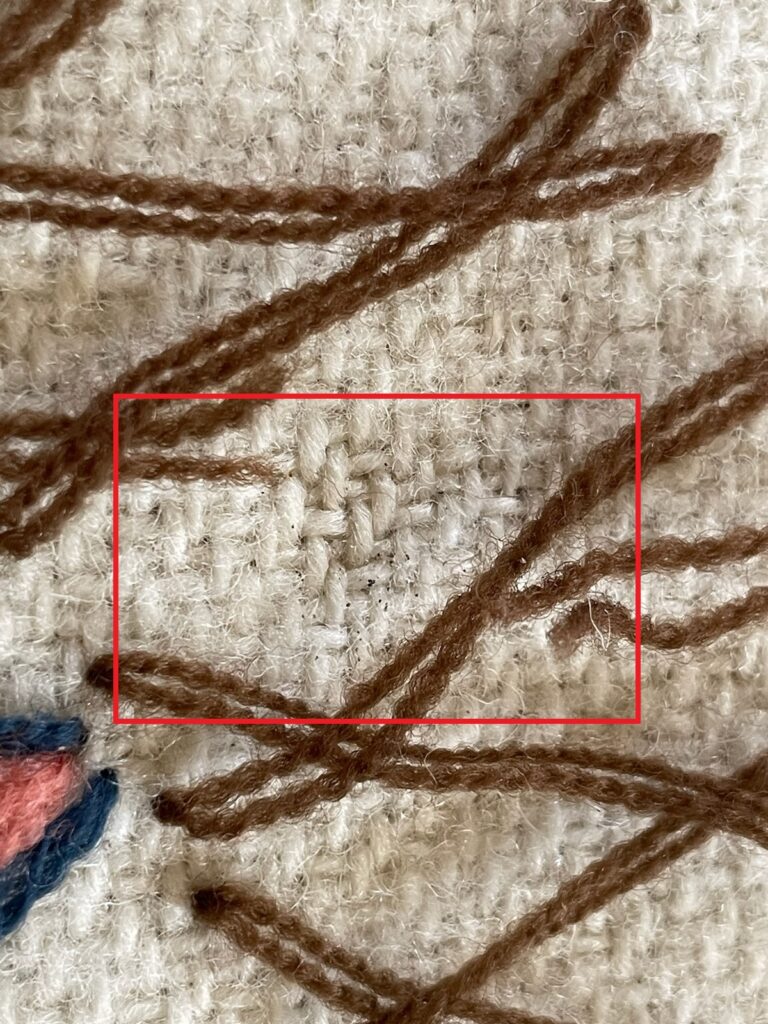

The best way of preventing a moth infestation is to keep the moths from coming into contact with your collection in the first place. But since no museum collection lives in a bubble—and historic house museum collections certainly don’t—monitoring the museum and its collection for signs of an infestation will keep damage to a minimum. Whenever an adult moth is spotted, look for the origins of the infestation: anything protein-based (wool and silk textiles, fur, taxidermy mounts) could contain larvae. Holes, webbing, and frass—small granular pellets the same color as the substance being consumed—are all indicators of an active infestation. Once an infestation is detected, it should be dealt with quickly: the affected item(s) should be quarantined from the rest of the collection, and the appropriate moth-killing method selected.

There are three ways of interrupting the clothes moth’s life cycle: freezing, fumigation, and pheromone traps. Freezing and fumigation work for eggs, larvae, and adult moths, while pheromone traps primarily capture adult male moths, ideally before they procreate. At Dumbarton House, we decided to combat our infestation using two methods: anoxic fumigation and pheromone traps.

Anoxic fumigation works by placing the affected object in a low-oxygen microclimate, effectively killing any pests present, regardless of their life stage. Unlike freezing, which might only send the moths into hibernation if not done correctly, anoxic fumigation has a high success rate, and poses no danger to the object. Downsides, however, include the longer supply list and a slightly more hands-on process: a microenvironment needs to be created out of a vapor-proof barrier, ensuring that no outside oxygen leaks back in. For larger objects, the chamber can then be flushed with nitrogen before the oxygen absorber is added.

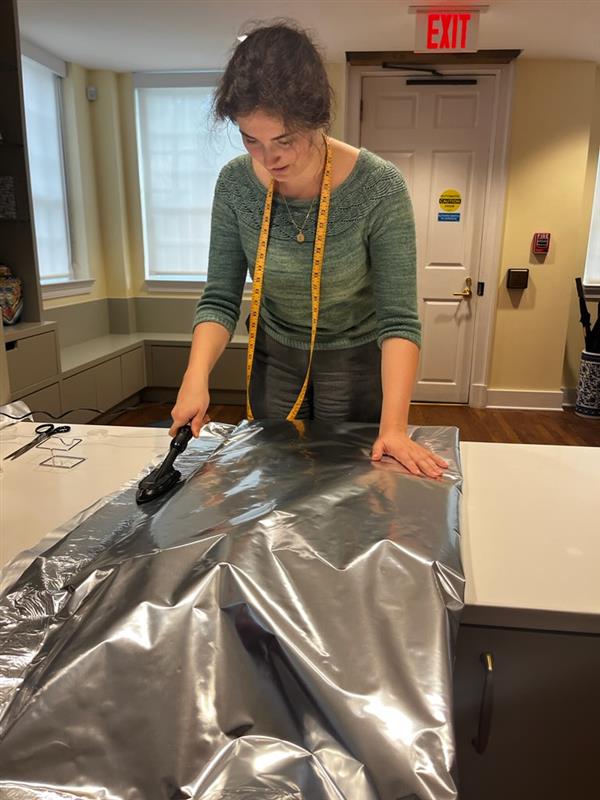

Undeterred, we ordered our supplies: vapor-proof barrier film (we used Marvelseal), Ageless ZPT-3000 oxygen absorbers, and a tacking iron. The Marvelseal was cut out to an area slightly larger than the blanket being treated, and the blanket was then sealed inside its chamber, leaving an opening large enough to insert the oxygen absorbers. While our calculations determined that eight packets of ZPT-3000 would be necessary for the size of our microenvironment, the recommendation that an additional 50% to 100% be added to ensure effectiveness meant that a total of 14 packets were used. The opening was sealed, the bag was dated, and we placed the blanket in an office where it could remain undisturbed for the requisite 10 to 12 days.

Once the blanket was unsealed, it was vacuumed to remove any dead eggs or larvae, and returned to the Best Chamber, where it remains on view. But since pest management is an ongoing process, rather than a one-and-done situation, we still have traps set in all museum rooms and collections storage, to allow us to continue monitoring insect and pest activity.

Written by Curator of Archives & Collections, Isabella Kiedrowski

August 2025

Resources :

Conserve-O-Gram Volume 3 Issue 6: An Insect Pest Control Procedure (The Freezing Process)

Conserve O Gram Volume 3 Issue 9: A Treatment For Pest Control (Anoxic Environments)

Conserve O Gram Volume 3 Issue 11: Identifying Museum Insect Pest Damage

Comparison of Treatment Methods – Canada.ca

Moth Seeks Wool: A Tale of Desire, Pheromones, and All That Frass | The Art Institute of Chicago

Webbing Clothes Moth: What to know

Supplies (As of 2025):

Ageless ZPT Oxygen Absorbers: Conservation Support Systems – Ageless ZP Oxygen Absorbers

MarvelSeal: https://masterpak-usa.com/products/marveelseal-r-360